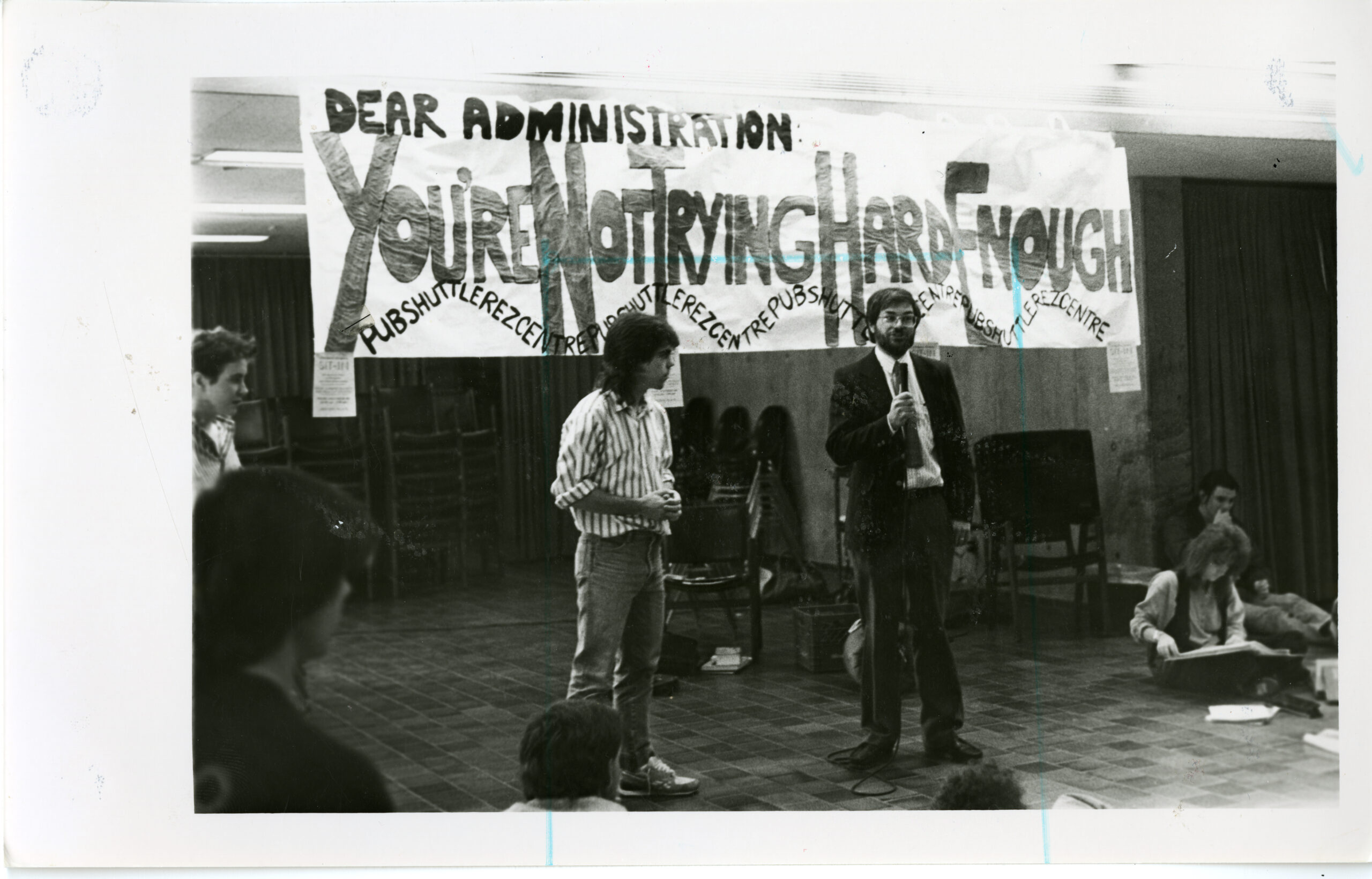

Universities often function as hotbeds of political activism and social transformation. It isn’t difficult to see why: students, driven by a profound sense of social responsibility and the exciting prospect of a better tomorrow, utilize their academic environment as a platform to engage in critical discourse and advocate for socioeconomic change. Thus, some of the world’s most prominent political movements have been bolstered by substantial student support: the 1976 Soweto uprising in South Africa, 1980 Gwangju uprising in South Korea, and 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in America are but a few examples. However, the inherent intensity of activism — that is, the physical and emotional toll exacted by the relentless pursuit of justice — can lead to many activists being overwhelmed by feelings of desperation and despair. This is a phenomenon known as “activist fatigue.” Such fatigue can have a particularly pronounced effect on students who, already burdened by the weight of societal expectations and personal responsibilities, may begin to feel hopeless about the cause for which they are fighting, sometimes to the extent that they may wish to abandon their cause completely. How, a fatigued student might wonder, do I know that all my efforts will make a difference at all?

While there has never been an easy answer to this question, one can look for inspiration and reassurance in examples of local activism and the outcomes thereof, including campaigns that originated and gained substantial traction at UTSC. The school’s Amnesty International group is a particular case in point.

Amnesty International (often abbreviated as AI) is one of the world’s foremost non-governmental human rights organizations, dedicated to protecting the fundamental rights of individuals worldwide and bringing about justice for whom those rights have been violated. The organization was founded in England in 1961 and spread to Canada as soon as 1963, gaining particular support from students on post-secondary campuses across the country (Amnesty International, “Who We Are”; Tapper 2002); the students at Scarborough College were no exception. The College’s chapter of AI was established in the mid-1980s, led by Professor Michael Bunce and consisting of students, staff, and faculty committed to raising local awareness about AI’s efforts, including the organization’s focus on “prisoners of conscience” (Bunce 1987). AI defines such individuals as follows:

“Someone who has not used or advocated violence or hatred in the circumstances leading to their imprisonment but is imprisoned solely because of who they are (sexual orientation, ethnic, national or social origin, language, birth, colour, sex or economic status) or what they believe (religious, political or other conscientiously held beliefs).”

(Amnesty International, “Detention and Imprisonment”)

Many of these prisoners are arbitrarily detained and denied access to legal officials or family members. They are also usually imprisoned in horrendous conditions and subject to torture, as well as various other human rights violations, therein.

In 1987, Scarborough College’s AI group was assigned a prisoner of conscience on whose behalf the group was to campaign: Park Hyun-Su, a “student and member of the student council at Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea” (Bunce Oct. 1987). Park was sentenced to 18 months in prison for publicly expressing his views on the current state of political affairs in South Korea, with Korean officials refusing to reveal where exactly Park was being held and in what conditions (Bunce Oct. 1987). His situation was worrisome, to say the least, especially when viewed in light of the then-ruling regime’s documented mistreatment of other student activists like Park. Students at Scarborough College thus embarked on a campaign raising local awareness of Park’s case and advocating for his release, collecting donations and sending hundreds of letters on his behalf to both the Korean government and Yonsei University (Bunce 1988). In the age before the widespread use of the internet and social media, this was the only way to have local voices heard hundreds of miles across the globe; one could only hope that these voices were also actually being listened to.

As is typical in such campaigns, the Scarborough College AI group received no formal communications or replies from either the Korean government or the university. One can imagine how hopeless these students must have felt, writing letters that they didn’t know would be read for a person who they couldn’t confirm was even alive; however, just when things began to seem bleak, news arrived that changed everything. In March 1988, the College’s AI group received word from Amnesty International headquarters that Park had been released and his case was officially closed by the Korean government! Thus, Park Hyun-Su, after enduring what was likely an incredibly difficult time in prison, was finally a free man again (Bunce 1988).

While we ultimately can’t know why the Korean government decided to release Park when they did — even the Canadian government’s file on the case is restricted and currently unavailable for public viewing — one hopes that the letters sent by Scarborough College’s AI group were at least somewhat influential in the decision, constituting a form of external pressure on the South Korean government to do right by their citizens and preserve the integrity of free speech. Had Scarborough students simply pushed Park aside as a lost cause, it’s possible that he would have been left to rot in a prison cell somewhere, his story left untold; in this way, Park’s case works to show us the importance of persistence and hope in activism, both on a local and international scale. Although fighting for such cases can feel hopeless at times, to lose hope in their viability is tantamount to abandoning them outright; thus, to continue hoping is an act that is both strategic and necessary to successful activism. This reminder is especially important for student activists wondering about the effectiveness of their efforts: remember that it is hope that gives us the courage to continue living despite life’s horrors and the world’s endless cruelties. As we continue to live, so we must continue to hope — for ourselves, for people like Park, and for the kinder, more just world that we will build together.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. n.d. “Detention and Imprisonment.” Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/detention/.

Amnesty International. n.d. “Who We Are.” Amnesty International. https://amnesty.ca/who-we-are/.

Bunce, Michael. 1987. “Increase Awareness at Amnesty Week.” The Underground, Jan. 20, 1987. Retrieved from University of Toronto Scarborough Library, Archives and Special Collections, Memory Collection, Identifier 61220/utsc12024. https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:61220/utsc12024.

Bunce, Michael. 1987. “Help Amnesty Find Park Hyon-Su.” Spectrum Vol. VII, No. 2, Oct. 7, 1987. Retrieved from University of Toronto Scarborough Library, Archives and Special Collections, Memory Collection, Identifier 61220/utsc11883. https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:61220/utsc11883.

Bunce, Michael. 1988. “Amnesty Secures Release of Park Hyon-Su.” Spectrum Vol. VII, No. 9, Mar. 16, 1988. Retrieved from University of Toronto Scarborough Library, Archives and Special Collections, Memory Collection, Identifier 61220/utsc11890. https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:61220/utsc11890.

Tapper, Lawrence. 2002. “Amnesty International Canada (English Speaking), R8298, Finding Aid No. 2284.” National Archives of Canada. https://data2.archives.ca/pdf/pdf001/p000000798.pdf.