Arguably no situation has thrown postsecondary students and universities across Canada into as much confusion as the current COVID-19 pandemic. In an attempt to limit the spread of the virus over the past few months, most, if not all, of Canada’s major universities urged their students to move out of on-campus residences, including the University of Toronto, York University, and McMaster University (Teotonio 2020). Speaking to the U of T experience in particular, though, the continued burden of academic stress and lack of physical access to the university means that many students, myself included, are experiencing a newfound estrangement from the university community — we find ourselves pressured to continue to perform academically without many prospects of the relief that we would normally find within the university environment amongst other students and supportive faculty. The more immediate concern here, though, is that many students, both domestic and international, who rely on student residences for secure housing throughout the year have been left in residential limbo — though those without a definite place to go have been allowed to stay in residence, what will happen when they inevitably have to leave, either because of a new influx of first-year student residents at the beginning of the next academic year or another circumstance? Now more than ever, then, we’ve come to see how crucial access to residence is for many: not only does it provide students with basic resources, such as the internet and running water, but it also provides necessary emotional support via an expansive community network, which, in such an unprecedented sociopolitical climate, is vitally important to our well-being. The absence of this latter support is being especially felt at UTSC, the small size of which has fostered tight-knit student and faculty connections over the years, particularly amongst those of us living on-campus.

Oddly enough, though, UTSC, formerly known as Scarborough College, was not initially envisioned as a residential campus. Original plans for the college instead only included space for traditional teaching, labs, administration, a library, common rooms, a cafeteria, and physical education, with no land explicitly designated for residences, so when the college began to offer its first courses in 1964, nearly all students, regardless of where they were coming from, were commuters (as cited in Ball 1989: University of Toronto, Off-Campus College Committee 1963).

It was only in May 1966 that plans to add two residences to accommodate 250-300 students were made official, with the passing of the Presidential Council’s Preliminary Proposal. Even then, though, residences were not a major concern for the college; in fact, the Proposal explicitly stated that “it is, and must remain, a primary purpose for Scarborough College to care for the majority of its student population, ie. for the non-residents” (Scarborough College, University of Toronto 1966, 2)! This isn’t necessarily surprising; one of the reasons why the University had chosen to build the College in Scarborough, as outlined in the Proposal, was because the area was expected to be rapidly populated with families in the coming years, so most of the college’s students would be locals (Scarborough College, University of Toronto 1966, 1). Hence, while other schools were focused on making residences the heart of their student life, Scarborough College had no plans to do so. Despite this, the residences filled up quickly, and there was soon demand for more: by 1968, the Scarborough Village Co-Op Association had to be formed “in response to student pressure for some form of local housing, and to alleviate the 9 to 5 commuter atmosphere of the college” (Scarborough Village Co-Op Association 1968). The Association temporarily took advantage of nine houses in the areas surrounding the college that the university had expropriated but had no immediate use for, and opened them up for student accommodation. Here’s the astounding part: residents had the choice of single or double rooms at the rates of only $11 per week for a double, and $14 per week for a single (Scarborough Village Co-Op Association 1968)! These days, you can’t even buy a single bedsheet, let alone an entire bedroom, at those prices.

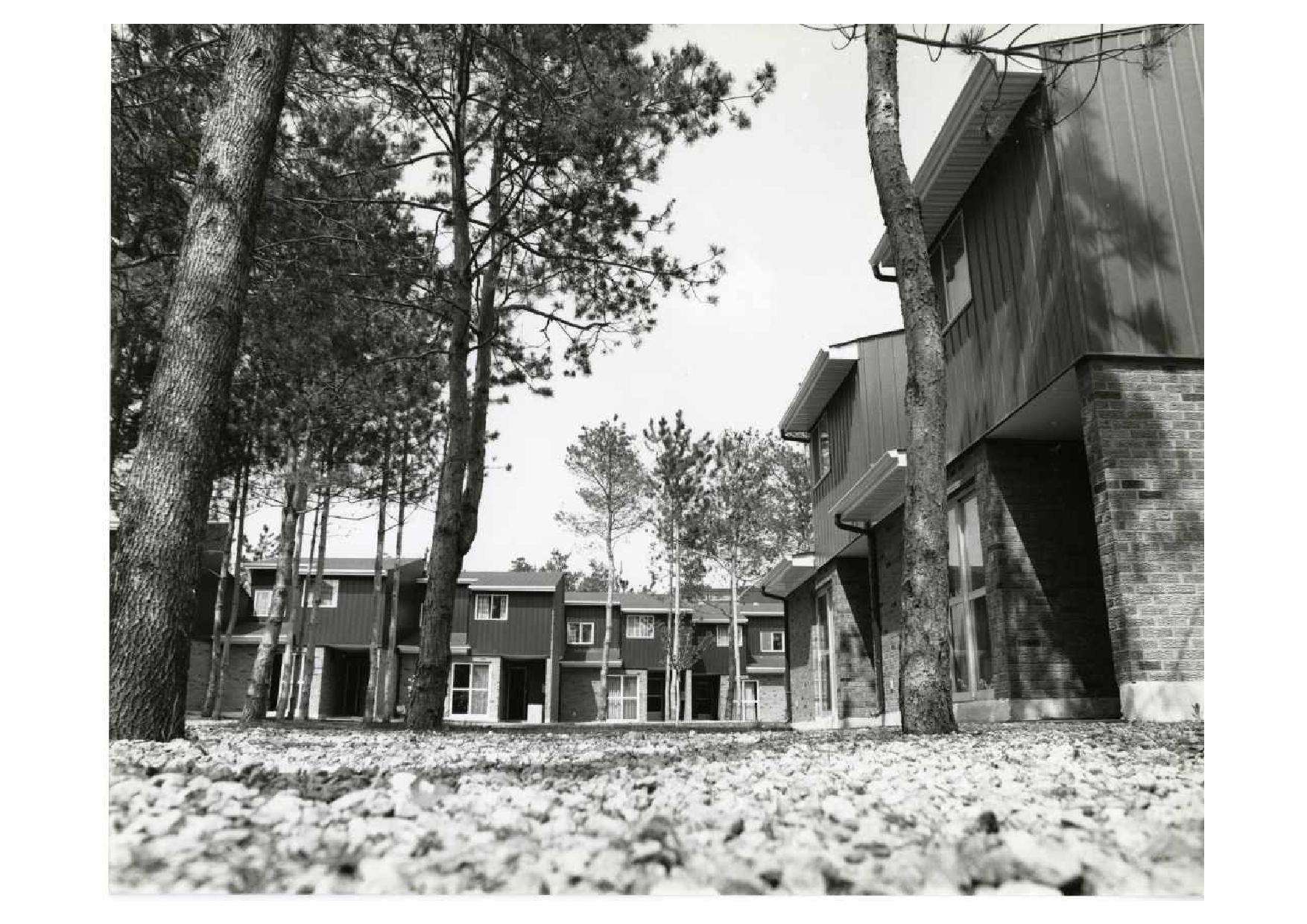

Unsurprisingly, it didn’t take very long for these rooms to fill up, and soon, students were again in need of more residential space. This time, though, they were more vocal about it: in October 1968, three Scarborough College co-eds held a sleep-in outside of the main building of the College to protest government delays in approving student residences (Murray 1968). In a move that was sure to turn more than a few heads, the protestors nicknamed their camp “Davisville” after William B. Davis, Ontario’s then-Minister of Education, and finally, in 1971, five years after the initial proposal, designs were approved for the construction of a series of townhouses to accommodate 250 more students (Murray 1968; Ball 1989). These were made available for accommodation in 1973, at the rates of $645 for a single room and $625 for a shared double room (Scarborough College 1974).

However, the struggle for student residences wasn’t over just yet: by October 1984, the existing residence model was no longer enough to accommodate all those in need of a place to stay, and new residences were still under construction, so a letter was sent by the College to local churches, newspapers, and radio stations asking Scarborough residents to board students from September until the end of the year. This is where we really get to see the unity of the Scarborough community shine: people “responded overwhelmingly” to the letter and “twice as many” offers poured in, enough to comfortably place all the students (“Community Responds to College’s Need for Extra Housing” 1984). Hence, for the first few months of the 1984 academic year, student residents had the unique opportunity to steep themselves in the Scarborough community in a way that was more intimate than ever before: by literally living in and as a part of it! Finally, by December of that year, the 36 new residences were made available, priced at the average rates of $1020 for a large single room, $1005 for a standard single, and $955 for a double room (Scarborough College, University of Toronto 1981). In 1992, 142 new townhouse beds were added to the residence accommodation, built on the west side of campus, and more recently, 2003 saw the opening of Joan Foley Hall, a four-story building that offers accommodation for 230 students in apartment-style suites (Ball 1989; University of Toronto Scarborough 2003).

Fast forward to today, and these housing facilities continue to serve students at UTSC, alongside the newer option of Centennial Place, and have become iconic cornerstones of the UTSC campus. For many students, these facilities provide a safe space to live, learn, and relax — but what happens when access to this space becomes unexpectedly restricted due to a global pandemic? As the 2020-21 academic year approaches with a university-wide commitment to online learning and the UTSC campus, as a consequence, remains largely closed, many students find themselves increasingly isolated as we struggle with the academic, financial, technological, and emotional challenges brought upon us by COVID-19. The weight of these challenges can be truly crushing at times, and the need for a sense of community and support has become crucial for students. If and how the university will provide us with this support remains uncertain, but one thing is for sure: there really is no place like home!

Bibliography

Ball, John L. 1989. The First Twenty-Five Years. Toronto: Scarborough College, University of Toronto.

“Community Responds to College’s Need for Extra Housing.” 1984. Scarborough College Spectrum, October 3, 1984.

Kalvapalle, Rahul. 2020. “U of T provides support to students who must stay in residence during COVID-19 outbreak.” U of T News, March 20, 2020. https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-provides-support-students-who-must-stay-residence-during-covid-19-outbreak.

Murray, Doug. 1968. “Scarborough sleeps in.” The Varsity, October 9, 1968.

Scarborough College. 1974. University of Toronto Scarborough College Calendar 74-75. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Scarborough College, University of Toronto. 1966. Residences for Scarborough College: A Preliminary Proposal. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Scarborough College, University of Toronto. 1981. Services for Students Booklet. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Scarborough Village Co-Op Association. 1968. “Scarborough Village (Co-Op) Housing.” In Student Handbook 1968, edited by Scarborough College. Toronto: University of Toronto.

“Student Residences”. n.d. University of Toronto Scarborough Library, Archives & Special Collections, Memory Collection, Archive File 2012-001C-6-1-52. https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:61220/utsc10569.

Teotonio, Isabel. 2020. “Students being urged to move out of residences due to COVID-19 fears.” Toronto Star, March 17, 2020. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/03/17/students-being-urged-to-move-out-of-residences-due-to-covid-19-fears.html.

University of Toronto Scarborough. 2003. “First New Residence in 11 Years Opens at UTSC.” November 11, 2003. https://utsc.utoronto.ca/news-events/archived/first-new-residence-11-years-opens-utsc.

(As cited in John L. Ball’s The First Twenty-Five Years, 1989) University of Toronto, Off-Campus College Committee. 1963. First Estimate of Space Requirements for Two Off-Campus Colleges in the University of Toronto. Toronto: The Committee.